December 15, 2020

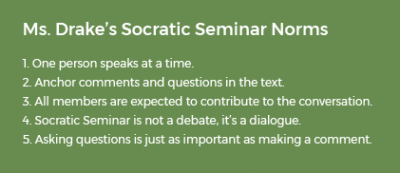

Sixteen faces appear on Zoom as Upper School English teacher Lauren Drake begins her Western and Global Literature course. It’s a Wednesday afternoon and these tenth graders listen patiently as Drake explains how the main item on today’s agenda will work; the class’ first Socratic Seminar of the quarter. Today’s Socratic Seminar is a comparison of Mary Shelley’s “Frankenstein”, Plato’s “Allegory of the Cave”, Ralph Waldo Emerson’s essay “Nature”, and a collection of William Wordsworth poetry. Drake explains the grading rubric, recaps the seminar’s norms, and reminds students to think about the space they inhabit in group discussions. Then it’s go time and students jump right in, starting with an examination of prompt one, a comparison of the uses of light and dark imagery in “Allegory of the Cave” and “Frankenstein”.

Sixteen faces appear on Zoom as Upper School English teacher Lauren Drake begins her Western and Global Literature course. It’s a Wednesday afternoon and these tenth graders listen patiently as Drake explains how the main item on today’s agenda will work; the class’ first Socratic Seminar of the quarter. Today’s Socratic Seminar is a comparison of Mary Shelley’s “Frankenstein”, Plato’s “Allegory of the Cave”, Ralph Waldo Emerson’s essay “Nature”, and a collection of William Wordsworth poetry. Drake explains the grading rubric, recaps the seminar’s norms, and reminds students to think about the space they inhabit in group discussions. Then it’s go time and students jump right in, starting with an examination of prompt one, a comparison of the uses of light and dark imagery in “Allegory of the Cave” and “Frankenstein”.

Different schools have their own unique way of engaging students in learning through classroom discussion. For some, there’s the Harkness Table, for others, the Fishbowl Model, and still others use the Jigsaw Method. At MPA, Upper School humanities teachers use the Socratic Seminar to create engaging, hands on, discussion based learning opportunities that facilitate deep dives into complex content knowledge.

Socratic Seminars, named for Greek philosopher Socrates and his Socratic Method, are more formal, text based classroom discussions in which the teacher poses open-ended questions to the group. Students listen and respond to classmates’ comments, think critically about the text themselves, and communicate their own thoughts within the group. At MPA, Socratic Seminars are built upon students’ commitment to respectful discourse, exploration of difference, cohesive cooperation and civil, intelligent examination. Hear from three faculty members, Lauren Drake (English), Sarah Mohn (English), and Summer McCall (Social Studies), as they share how Socratic Seminars happen in their classrooms.

Lauren Drake

We do two types of whole class discussions. One is more of a daily participation discussion where students journal about a text and discuss it in small groups, and then we’ll move our desks into a circle and share thoughts. They receive a point each time they share. In this way, they don’t raise hands and it is a great way to discuss organically.

We do two types of whole class discussions. One is more of a daily participation discussion where students journal about a text and discuss it in small groups, and then we’ll move our desks into a circle and share thoughts. They receive a point each time they share. In this way, they don’t raise hands and it is a great way to discuss organically.

I also do Socratic Seminars in my class as a formal assessment that I use at the end of a unit. This is where students have to prepare for questions ahead of time and I am grading them not just on how often they speak, but what they say and how they use evidence. The first photo is from a Socratic Seminar in 2019. As you can see, when not on Zoom, we are sitting in a circle and students are facilitating the discussion themselves. I am almost always completely silent during these discussions.

Summer McCall

I went to a professional development seminar about 10 years ago on the Socratic Seminar and we’ve been doing it in my classes ever since. For me, Socratic Seminars are a way to facilitate class discussions by encouraging students to have dialogue back and forth between each other. They allow me to get to know the students incredibly well, and for the students to get to know each other incredibly well too. That’s why it’s so perfect for MPA. We tend to have warm discussions that are full of heart, the polar opposite of sterile.

My Socratic Seminars start with a complex reading of a primary source. For example, Simon Bolivar’s “Jamaica Letter” is part of our unit on Latin American history in tenth grade world history. Before the Seminar begins, we find themes like good and evil, security and progress, and instability and hope, and look at the document through those lenses. This allows students to interpret the passages in their own way before class discussion. In class, students connect in small groups or with partners, then we begin the large group Socratic Seminar discussion. It’s really amazing to see this. I have 14 students in the class, and they speak without stopping for 60 minutes. I do nothing more than a little facilitating. Sometimes, the students are nervous before the Socratic Seminar and I get emails the night before with questions about the format and how to prepare. But then after the discussion, everyone agrees that they not only understand the text that we are working with better, but they could teach it to another person. It really helps students decipher difficult primary sources.

World History 10 Socratic Seminar Student Notes

Sarah Mohn

Discussion is without a doubt the foundation of my classroom. At times, our discussions take the form of full class Socratic Seminars, and at other times, students discuss in small groups. We even have written discussions on butcher paper, when in person, or, while in virtual school, via a Schoology discussion. In my class, discussion is a path to make meaning of a text rather than a stage to demonstrate knowledge. My top priority is encouraging students’ growth in discussion skills. I track follow-up questions to see who is moving our conversation deeper. We mix up the format, rotating in small groups and using inner and outer circles to make sure everyone is contributing.

It’s been amazing to watch the students adapt to Zoom discussions as well. We do utilize break-out rooms so students can connect more deeply and frequently, but whole class discussion in the format of Socratic Seminars remains part of our curriculum. This week, my students engaged in a 45 minute discussion, in which together, they set goals for their own participation (regarding the asking of questions, the number of turns speaking, and the making of space for other voices) and managed it without hand-raising. I didn’t even have to be “directing traffic” as the teacher, so I was able to be a participant, instead of a manager. Watching their ah-ha moments in this discussion was the highlight of my week!

It’s been amazing to watch the students adapt to Zoom discussions as well. We do utilize break-out rooms so students can connect more deeply and frequently, but whole class discussion in the format of Socratic Seminars remains part of our curriculum. This week, my students engaged in a 45 minute discussion, in which together, they set goals for their own participation (regarding the asking of questions, the number of turns speaking, and the making of space for other voices) and managed it without hand-raising. I didn’t even have to be “directing traffic” as the teacher, so I was able to be a participant, instead of a manager. Watching their ah-ha moments in this discussion was the highlight of my week!